Bed Notes

There it is. Affixed to the wall. A blue-lined, white piece of paper torn from a writing tablet he bought her to record her new recipes. She had become skilled at creating her own recipes and “fixing” those written by others. Her kitchen had not been cooked in the last two years though. She stopped her cherished, family-chef duty when the memory and depression ailments could no longer be held at bay. The recipes were not really new. She had forgotten them. Then a television advertisement or some other cue stirred her memory so she remembered them anew. It was imperative she write them down before they returned to whatever place forgotten memories go.

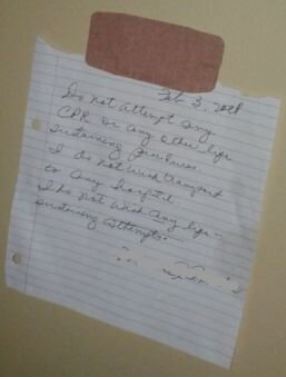

Instead of writing a recipe for blueberry pie, she wrote her bed notes. Plural, because each line was a single instruction. Three lines of dicta, separate in meaning but conjoined with her intent. She knows he is trying to put her in a hospital because he thinks she needs medical care, and perhaps psychiatric care; but she will not go. Nothing is wrong with me, she thinks. Nothing is wrong, she tells him. He reads her words on the recipe paper and is amazed by the neatness of her handwritten, blue-inked cursive.

Do not attempt any CPR or any other life sustaining procedures. I do not wish transport to any hospital. I do not wish any life-sustaining attempts.

There it is. Three bed notes she dated, signed, and stuck to the wall with a large Band-Aid because she could not find real tape. These notes rest above the hospital bed he bought her so she could get more rest. This bed was given from love but it is made to facilitate health care. There is a portable toilet next to it that he helps her get on and off. She still says nothing is wrong.

He reads the bed notes like a suicide letter, and he believes when the ambulance arrives that the paramedic will agree with him. Something is wrong. He is only trying to take her to a medical hospital. It’s not even a nursing home. It is a genuine hospital with real doctors. She has happily accepted his other salubrious offerings to improve the quality of her life. Yet, she refuses medical treatment with three lines.

He has watched her for too long wasting away in this bed. Anemic, not bathing, not sleeping, joints hurting, eye sight failing, blood pressure falling, oxygen level too low—but she thinks nothing is wrong. He knows the fact that she thinks nothing is wrong proves something is wrong. He knows after the ambulance takes her to the real hospital that she’ll get treatment, she’ll get better, and he’ll get back the woman he used to know. Of course they will take her, he thinks. People want to help other people. They will see her condition and immediately recognize her vital need for help. They will help him save her. And then when they move her from this bed to the back of the ambulance, he will take down her suicide note.

Two paramedics knock on the door. He lets them in. She sits up in the hospital bed, tells them her name, her birthday, the day of the week, the current U.S. president, and tells them to make sure they read her note. With a bony, arthritic finger, she directs the paramedics’ eyes to the bed notes just above her head. They slowly read the note and whisper to each other and then nod to her. Transport refused, the paramedics leave more quickly than they came. They leave without her.

And there he is. Staring incredulously at her bed notes that are still affixed to the wall.